|

|

What about Psammirises,

Pseudoregelias, and Falcifolias?

|

These

three relatively obscure groups of irises show enough similarity to

aril and bearded iris to periodically attract the attention of

enthusiasts interested in those groups. I have not (prior to this

article) included information about them on this site. The reason is

that, at least so far, they have not had any role in the tetraploid

fertile families of bearded, aril, and arilbred irises to which this

site is devoted. But for those curious about them, it may be of

interest to describe their relationships and history here.

These

three relatively obscure groups of irises show enough similarity to

aril and bearded iris to periodically attract the attention of

enthusiasts interested in those groups. I have not (prior to this

article) included information about them on this site. The reason is

that, at least so far, they have not had any role in the tetraploid

fertile families of bearded, aril, and arilbred irises to which this

site is devoted. But for those curious about them, it may be of

interest to describe their relationships and history here.

What are they?

These irises are all small in stature, with

some points of resemblance to both bearded irises and to arils.

Except for Iris humilis (formerly referred to as I.

arenaria), which has an enclave population in eastern Europe,

they are all native to the steppes and mountains of central Asia. The

psammirises (which means "sand irises") include I. humilis,

I. bloudowii, I. potaninii, and others. The best known examples

of the pseudoregelia group are I. hookeriana and I.

kemaonensis, and I. facifolia is (nearly) alone in a

grouping by itself. These irises do have beards; their foliage is

grassy, narrow, and wiry, and their rhizomes small and tightly

clumped. They have miniscule arils on their seeds. I shall mostly

focus on the psammirises, as this is the only group that was ever

frequently grown in gardens or used in hybridizing. I have grown and

bloomed I. potaninii (pictured at right) from a commercial

source, and germinated seeds of I. humilis that have yet to

grow and bloom here.

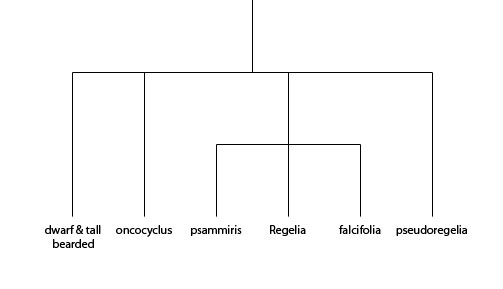

Here is the current scientific understanding

of their evolutionary relationship to other irises, based on

molecular DNA data:

In reading such a diagram, an analogy with a

human family tree may be helpful. The two aril groups, oncocyclus and

Regelia, are like siblings, more closely related to each other than

to any of the other groups. The bearded irises (both the dwarf

bearded species and the tall bearded ones) are their "first

cousins". The psammirises are one step further removed, "second

cousins", as it were, to both the arils and the bearded irises. The

next step further out we find "third cousins" I. dichotoma and

I. domestica, which you may recognize as the parents of the

popular garden plant I. X norrisii. Other groups in the

genus are even more distant relations.

So these irises are neither bearded irises

nor arils (as the term is currently used), but are more closely

related to both those groups than any other species in the genus. At

one time, their relationship to arils and bearded irises was thought

to be even closer. It is worth reviewing this history, as it has

influenced how iris enthusiasts have treated them over the last

century.

Classification History

W. R. Dykes, in his monumental 1914 monograph

The Genus Iris, treated each of these three groups

differently. He placed the psammirises among the bearded irises, in

two separate groupings, alongside the dwarf and TB species. He placed

the pseudoregelias in a group by themselves, separate from

oncocyclus, Regelia, and bearded irises but related to all three.

I. falcifolia he simply listed as a Regelia, alongside I.

stolonifera and I. korolkowii, without comment.

Dykes's placement of the psammirises among

the bearded species prompted dwarf iris breeders to take an interest

in them, and about twenty hybrids between them and the dwarf bearded

cultivars of the time (mostly forms of I. lutescens) were

created, registered, and introduced into commerce.

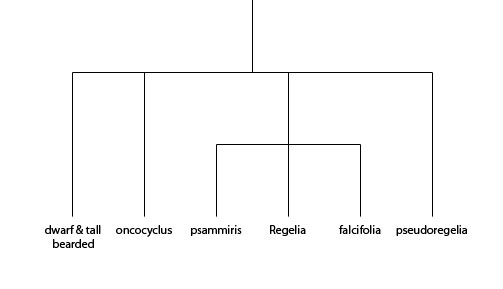

This was superseded by the classification of

Lawrence and Randolph (1959), which was the most influential

treatment for most of the English-speaking world in the mid-twentieth

century. This is the system used in the essential reference The

World of Irises, published by the AIS in 1980. Here is a

diagram of this system:

Here you can see that the psammirises and

facifolias have been placed in close relationship with the Regelias,

closer to them than even the oncocyclus. The pseudoregelias remain in

their own category, much as in Dykes's system. Around this same time,

the iris hybridizer and nurseryman Lloyd Austin popularized the term

"aril" to refer to the irises with arillate seeds, particularly the

oncocyclus and Regelias that were the object of much attention at the

time, but also including our three groups, based on the presence of

arils on their seeds. Just as Dykes's treatment of the psammirises

prompted iris lovers to regard them as dwarf bearded species,

Lawrence's treatment and Austin's promotional efforts prompted people

to think of them as arils, kin of the Regelias in particular. The

korolkowii/humilis hybrid 'Koviar' (1970) is the sole example

of a hybrid registered from aril/psammiris breeding. The Aril Society

International, founded in 1957, classified all three groups as arils,

under the influence of Austin's terminology and Lawrence's

classification. Indeed, it would have been inconsistent to exclude

the psammirises and falcifolias in particular, given their perceived

closeness to the Regelias. The psammiris/dwarf hybrids were treated

as regeliabreds at this time, and for that reason I have included

entries for them in my Checklist

of Arilbred Dwarfs and Medians.

The next major revision of the classification

of the genus came with Brian Mathew's publication of Iris in

1989. He determined there was no compelling evidence to connect these

irises with the Regelias in particular, and set out the following

system:

This system may be seen as an expression of

humility: Mathew knows that the oncocyclus, Regelia, bearded

irises, and our three groups are all related to one another - somehow

- but does not commit to anything more specific than that. The Aril

Society took notice of the change and restricted its scope to the

oncocyclus and Regelias. From this point, the psammirises,

pseudoregelias, and falcifolias were no longer "arils", although they

might still be called "arillate" in reference to the morphology of

their seeds. It is worth noting that arils are found on the seeds of

other irises, such as the Junos, that are not particularly related to

oncocyclus and Regelias, and even on many plants that are not irises.

They are a trait associated with seed dispersal by ants and other

insects, not necessarily a marker of relatedness.

When we now look at the relationships

established by modern DNA analysis, we can see a trend in the

understanding of these irises over the past century or so. Initially,

the temptation was strong to connect them with the more familiar

bearded and Regelia irises. Dykes could matter-of-factly list I.

falcifolia as a Regelia species, and all the psammirises as dwarf

bearded species, right along with I. pumila, I. lutescens, I.

suaveolens, and the others. Lawrence connected the psammirises

and falcifolias with the Regelias, but gave them their own

pigeonholes in that association. Mathew disentangled them from the

Regelias. Finally, the DNA analysis places them even farther afield.

We now know that the arils (oncocyclus and Regelia) are closely

related to each other, and that their next nearest relations are the

bearded irises, not the psammirises. The psammirises and their kin

are also related to both arils and bearded irises, but more

distantly. They should not be associated with either arils or

beardeds in particular, but are part of a larger clan that includes

all those groups.

Hybridizing Potential

As mentioned above, psammirises have been

successfully crossed with both bearded irises and arils. I am not

aware of any crosses involving the pseudoregelias or

falcifolias.

No fertile seedlings have resulted from

either type of cross. ('Keepsake' did produce a pentaploid from an

unreduced gamete for Paul Cook, when crossed with a TB.) 'Tiny

Treasure' (Hillson, 1943) has a registered parentage of 'Ylo' X I.

humilis, and 'Ylo' is a humilis/lutescens hybrid. However,

a chromosome count was performed and the result was not consistent

with the parentage, which was likely recorded in error.

The psammiris/lutescens hybrids have a

distinct charm, and some are still being grown. Early dwarf

hybridizers were attracted to I. humilis and I. bloudowii

for their flaring form, clear yellow color, and the habit of the

faded flowers to curl up into tight corckscrews, rather than just

going limp as bearded irises do. When Jay Ackerman succeeded in

crossing I. humilis with I. pumila in 1956, it was a

sensation in the world of dwarf iris enthusiasts. The

DIS Portfolio embellished its drab mimeographed pages

with unprecedented color photos, attached by staples. I think

interesting results could be achieved by crossing the psammirises

with modern SDBs, although hybridizers seemed to lose interest in the

psammirises once the SDBs came into their own. The last

bearded/psammiris hybrid ('Sunaire') was registered in

1969.

The psammirises used in early hybridizing

have chromosome counts of 2n=22, although more recent counts of

different collected forms more often show 2n=28. I. hookeriana

(Pseudoregelia) was counted as 2n=24. I. falcifolia is

2n=18. The psammirises having the same chromosome count as the

diploid Regelias added support to the conjecture that these two

groups were closely related, but is now viewed as coincidental, as is

I. hookeriana having the same count as diploid TBs. As

discussed elsewhere on this site, it is not chromosome number per

se but rather the homology (chemical and structural similarity)

of the chromosomes that is important in meiotic pairing.

The compatibility of psammirises with both

bearded irises and arils offers some hope to hybridizers, but fertile

offspring are expected only at the tetraploid level, barring a rare

unreduced gamete from a diploid hybrid. As there are no known natural

tetraploids among the psammirises or other related groups, any work

in this area will have to wait until someone induces tetraploidy in

them artificially, or else raises thousands of seedlings in a

brute-force (a la C. G. White) approach to generating accidental

tetraploids or amphidiploids. Since these irises lack the intrinsic

drama of the spectacular oncocyclus to inspire such laborious

undertakings, it is likely that they will remain a footnote in the

history of iris breeding for the foreseeable future.

If I had the resources and inclination to

pursue a hybridizing program with the psammirises, I would

probably put aside the task of crossing them with bearded irises or

arils, which looks to be a dead end, and instead cross them amongst

themselves to bring out whatever latent genetic potential is in the

group and breed fertile plants at the diploid level with desirable

garden qualities.

Tom

Waters

December 2017

updated January

2018

Unless otherwise noted, all text

and illustrations copyright Tom Waters and all photographs copyright

Tom or Karen Waters. Please do not reproduce without

permission.

These

three relatively obscure groups of irises show enough similarity to

aril and bearded iris to periodically attract the attention of

enthusiasts interested in those groups. I have not (prior to this

article) included information about them on this site. The reason is

that, at least so far, they have not had any role in the tetraploid

fertile families of bearded, aril, and arilbred irises to which this

site is devoted. But for those curious about them, it may be of

interest to describe their relationships and history here.

These

three relatively obscure groups of irises show enough similarity to

aril and bearded iris to periodically attract the attention of

enthusiasts interested in those groups. I have not (prior to this

article) included information about them on this site. The reason is

that, at least so far, they have not had any role in the tetraploid

fertile families of bearded, aril, and arilbred irises to which this

site is devoted. But for those curious about them, it may be of

interest to describe their relationships and history here.